W(h)ither the University Presidency? Part I

A brief history of the presidency through an organizational lens

While starting to write something on what kind of leader universities need as they reconsider who they are and wish to be, I came across a draft piece on university presidents that I wrote in 2014 but had never submitted anywhere. It is more detailed about the history of university presidents than I intended to write now, but remains to the point and its organizational perspective is worth emphasizing.

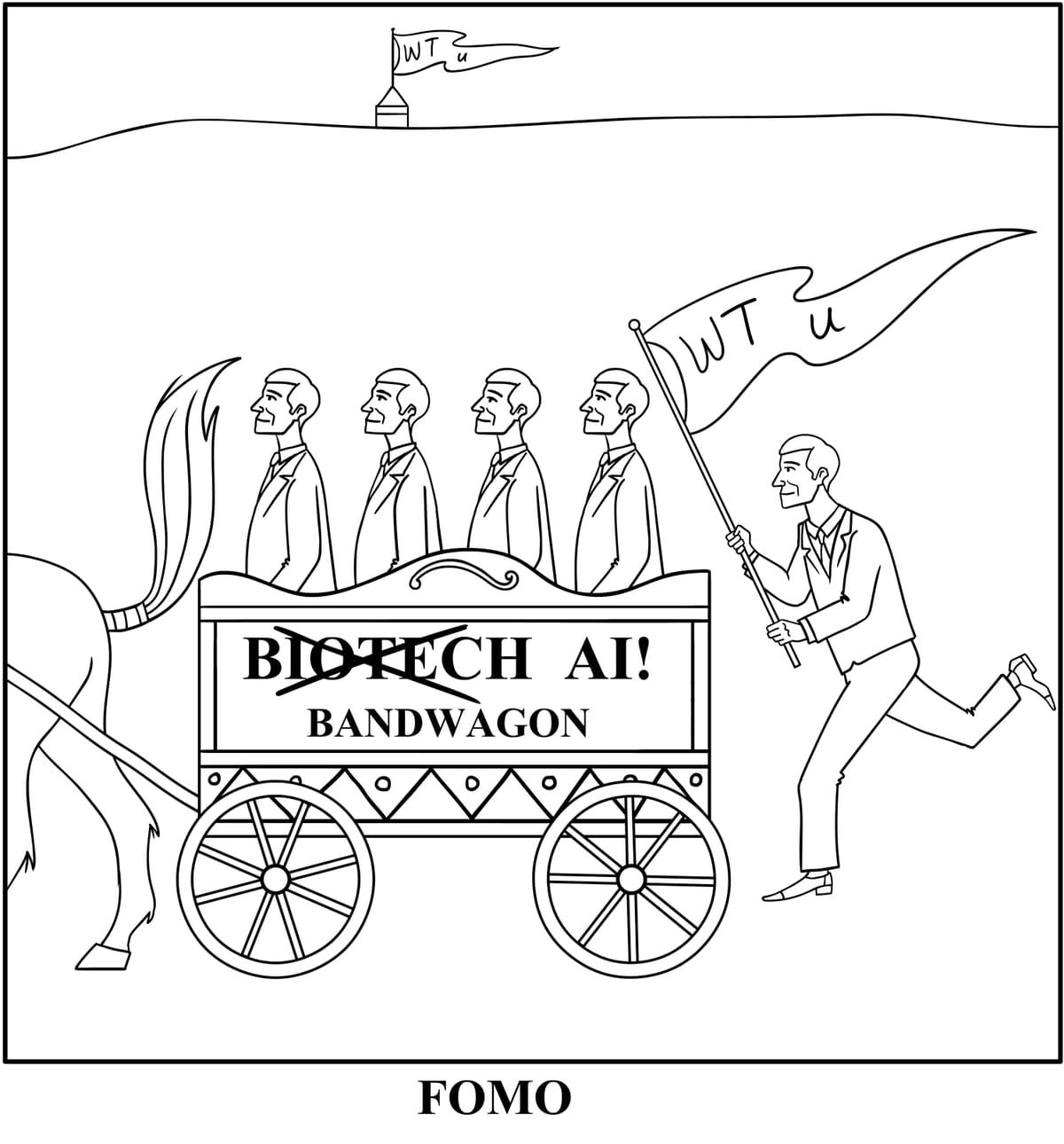

I reprint the first (historical) half of it here as a kind of introduction to a way of thinking about the presidency, contextualizing it over time, and in preparation for asking whether the categorical approach to recruiting—as documented here not only in higher education but also in business—is the most productive way to think about leadership needs now (see Note).

Excerpt from 2014:

“Over the past few years, there have been two much discussed governance stories in higher education. One has focused on presidential failures, scandals, and recruiting nightmares. The other has focused on critiques of and regulatory movements toward accountability in higher education. Both are continuing and visible sagas; no need to rehash here.

"But it may be a good time for some simple addition. Surprisingly, these two stories have never been linked, yet they are intimately related. Their co-occurrence transforms as: Presidential Crises + Public Policy Movements = President Model in Transition.

"The relationship between the characteristics of institutional presidency and public policy, particularly that prompted by perceived crisis, has been well demonstrated for the corporate world. In The Transformation of Corporate Control, Neil Fligstein traced the evolution of the chief executive role in corporate America over the course of a century and found that shifts in public policy, particularly government agendas and regulation, dictated the way firms were run, or what he called “the conception of control.” This characterization underscored the evidence that the efficiency and profitability assumptions of competitive market economics had little to do with firm strategy and structure (at least from an evolutionary view), and consequently the backgrounds and orientations of executives at the helm. Rather, change was a constructed result of interactions between large firms and states; was emulated by smaller, striving firms whether applicable to them or not; and was aimed at survival and protection of institutional interests. Only four conceptions of control, with their associated executive “type,” have been dominant in the American corporation. These are: direct, exercised by pre-regulation-era firms with narrow, definitive charters and exclusionary tactics; manufacturing, based on high production/low cost through forward and backward integration and oligopoly; sales and marketing, characterized by expansion, diversification, differentiation, and decentralization of related products; and finance, characterized by unrelated products and asset (not profitability) growth through acquisition, debt, and short-term manipulation of the stock price. In each case the background of the executive reflected the conception of control as a kind of operating ethos, and the new structure created the “market,” not vice versa. Fligstein attributed declining global competitiveness of U. S. firms to the more recent financial approach.

"In higher education, a remarkable analogy of changing ethos and presidential type exists, although stretched over a longer timeframe. It is even possible to use the same categories of control, as there are many parallels to higher education, adding perhaps one more, political, that has emerged from and overlaps with the financial model in recent years. The patterns of disciplinary background and skill set of those who have dominated administration in major research universities over time are generally consistent with changes in the public policy and institutional environment, which are linked. Naturally there are periods of transition where there are lags resulting in overlap of presidential types, and looking at background alone produces a substantial aggregate simplification of what is, after all, individuals. But given that recruiting itself tends to follow a profiling approach, understanding these core perspectives of presidents over time can be instructive.